By Linda J. Blumberg, Kevin Lucia, and Kennah Watts

The high cost of health care is front of mind for many American voters this election cycle, and policymakers across the political spectrum have floated reforms to bring down health care costs. However, identifying and advancing policies that truly deliver less expensive, high quality health care requires policymakers, researchers, and other stakeholder to understand how the health care system has become increasingly financially intertwined and riddled with incentives that drive costs ever higher, often at patients’ expense. In the last quarter century, the health care market has seen significant vertical and horizontal integration of health care providers and insurers, with considerable research that evidences how this consolidation leads to higher prices and lower quality of care.

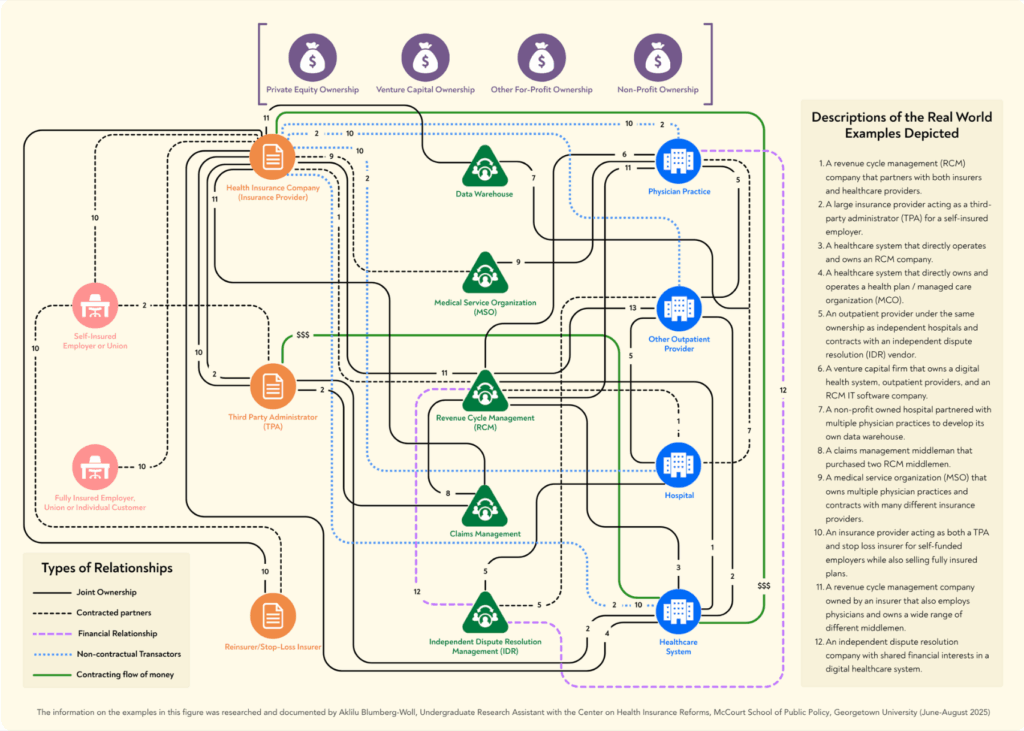

While these forms of integration are vital to understand and address, we must widen this consolidation picture further. The financial interests of providers, insurers, administrative entities, and other “middleman” businesses are now strongly aligned to increase health care spending through a complex web of common ownership, contracting arrangements, and financial deals which create an array of conflicts of interests and hidden flows of money. These strongly aligned interests and relationships collectively contribute to increased health care spending through a complex web of common ownership, contracting arrangements, and financial deals which create an array of conflicts of interests and hidden flows of money (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Complex Web: Illustrative Examples of Intertwined Financial Interests

The complexity is so tremendous that it is virtually impossible to capture the entire picture of the existing financial relationships, and that is the point––through opaque relationships and hidden practices, these entities operate without sufficient oversight or limits. Despite the challenges inherent in unwinding the components of the web, it is critical that we begin to do an accounting of the current nature of our health care eco-system to understand its implications for private and government spending on health care, and, ultimately, access to and quality of care. A big-picture understanding is also critical for designing and promoting public policy approaches to rationalize health care costs and promote access to high-quality medical services.

In a recently published expert perspective, we dive into this situation and demonstrate that the proliferation of administrative and financial middlemen collaborating or entwined with insurers, TPAs, and/or providers, as well as the interrelationships between insurers, TPAs, and providers themselves, all work against an efficient market equilibrium and, instead, inflate spending on health care goods and services.

Here we present a condensed version of this expert perspective, which focuses on medical benefits and the market for commercial insurance.

Growth in Spending on Private Health Insurance is Correlated with Growth in Administrative Costs and the Middlemen Market

Spending on private health insurance has grown considerably in the last decade. As total expenditures on private health insurance more than tripled from 2020 to 2023, so too did the net cost of health insurance, also known as administrative costs ($150.78 billion in 2023). This administrative spending outpaced the growth in private health insurance spending on physician and clinic services, retail drugs, and all other expenses collectively, except for hospitals. Although some of these administrative costs are necessary to run a health system, experts posit that at least half of health care administrative costs in the U.S. are wasteful.

This wasteful spending appears closely correlated to the size and scale of health care administrative and financial middlemen, an industry that has skyrocketed in size in recent years. In 2024, the market for only one type of middleman – revenue cycle management (RCMs) companies – was estimated at a value of $172.24 billion, and it is expected to grow by another 10 percent by 2030. The broader middleman industry includes, but is not limited to, RCMs, re-pricers, claims denial management firms, independent dispute resolution management companies, data warehouses, and point solution vendors. Each of these middlemen profit by increasing revenue for insurers, providers, and sometimes both, and the fees paid to them add to provider prices and/or the administrative costs baked into private health insurance premiums.

Multifaceted Market Failures Underscore Why and How this Complex Web has Arisen and Increased Costs

Several reasons explain how and why this web has grown so entangled: providers dominate many markets, insurers and third-party administrators (TPAs) have financial interests to keep spending high, and middlemen profit from repeated adjudication of claims and other fees associated with an ever more complex system. We explore each of these reasons briefly below, and additional explanation and examples can be found in the full expert perspective.

Many Providers Face No Constraints on Pricing in Private Markets and Use Various Tools to Maximize Revenue and Hold Down Input Costs

The research evidence is clear that as health care providers consolidate ownership with other providers—for example, multiple hospitals merging to form a chain or hospitals integrating with physician practices—the prices paid for their care increase and insurance premiums rise, with no commensurate increase in the quality of care or improved clinical outcomes. Health care providers can extract higher revenue through unfair billing practices like facility fees, and through various types of anti-competitive behavior that increase the average cost of medical claims, thereby increasing patient out-of-pocket costs as well as insurance premiums paid by consumers and employers. Anecdotal evidence indicates that, in order to secure their place in plans’ networks, consolidated providers have required insurance companies to guarantee the providers a minimum level of revenue across some or all of an insurers’ lines of business, and this may result in extra payments above the negotiated rate for a subset of services determined by the insurer.

In a competitive market, health care providers’ profit motive would not necessarily be problematic, as health care purchasers vying for market share could exert downward pressure on prices until an efficient equilibrium was reached. Purchasers are most often not in a competitive market, however, and this is not only because of horizontal and vertical integration among health care providers. Provider consolidation has been coupled with more varied types of consolidation of ownership and financial interests across health industry stakeholders. For example, insurers and TPAs have incentives to drive spending on claims upward, contrary to what some of their clients may expect. Because their incentives are significantly aligned with those of providers, many providers and insurers see the profit potential from integrating with each other as well.

Insurers Have Financial Interests in Keeping Health Care Spending High

While providers often have the market power to demand and extract high prices, insurers also have incentives to keep spending high. First, federal medical loss ratio (MLR) limits –– intended to prevent insurers from selling low-value plans –– have unintentionally contributed to higher prices: insurers make greater profits when provider prices are higher under their fully insured plans. Second, in some cases, the insurer and health care providers are owned by the same entity, creating financial incentives for the insurer to increase spending on those providers in particular. And third, major insurers have contracts with and sometimes share ownership or other business relationships with middlemen companies that increase the insurers’ own revenue and profits as claims increase.

Many TPAs Have Financial Interests That Tend to Increase Health Spending, and Employers Have Limited Choice in TPAs

Importantly, because employers are not purchasing health insurance in a competitive market, employers cannot “solve” these problems or disincentivize high spending from insurers or providers. The TPA market administers health plans for self-funding employers, and it is dominated by the BUCAs (Blue Cross affiliates, United, Cigna, and Atena), entities which have their own interests to increase financial relationships and claims costs. Lawsuits brought by employers and investigative journalism suggest that some TPAs then employ strategies hidden from employers – such as “skip” lists, cost-plan offsetting, shared savings, and more – to accrue billions of dollars in revenue at the expense of the employer, their workers, and a competitive market. These opaque agreements between TPAs, providers, and middlemen are often unknown or misunderstood by employers, the dominance of the BUCAs give even the largest employers few feasible alternatives, and the TPAs provide little information to employers about how their money is actually being spent.

Middlemen Make Money by Repeated Adjudication of Claims and Higher Costs

Amidst these provider, insurer, and TPA markets, middlemen entities have entered to further maximize profit for the other stakeholders and themselves. While middlemen entities promise greater efficiency and billing accuracy for their clients, the fees of this large and fast-growing industry are subsumed in insurance premiums and patient out-of-pocket payments, and there is growing concern of financial conflicts of interest and insufficient government oversight of their operations.

Middlemen are sometimes independent with financial interests tied to increasing revenue for providers or insurers through a system of fees; sometimes middlemen are subsidiaries of one of the stakeholders; and sometimes middlemen are owned by private equity firms that also own one or more other health care stakeholders. Some of the middlemen companies contract with both insurers and providers, promising increased revenue to both, and creating a system of repeated adjudication between the different arms of the same company, profiting themselves regardless of the outcome, with the incentive being for higher billing and greater numbers of disputes challenging the bills.

While some of the middlemen entities are long-standing members of the market, such as RCMs, new types of middlemen emerge wherever market advantages can be found. Take for example, HaloMD. This independent dispute resolution (IDR) management company arose only after the passage of the No Surprises Act and the creation of the federal IDR process. By handling the IDR process primarily for providers –– through dispute submission, negotiation, offer analysis, and more –– these entities profit from high-volumes of high payment determination awards. And so far, HaloMD has been quite successful: across all disputes, HaloMD has secured a median award of 934 percent of the qualifying payment amount (a proxy for in-network rates). These IDR management companies, like so many other middlemen, have a clear motivation to maximize reimbursement for providers, which will ultimately increase health care costs and overall spending.

Action is Needed: Left Untouched, The Complex Web Will Continue to Grow and Harm Patients

An intricately complex health care financial web is undoubtedly driving health care prices and aggregate spending upward. Left alone to market forces, spending will continue to climb, likely at accelerating rates. The heightened focus of health care entities on ownership and contracting relationships that increase revenue and profitability are likely to take an increasingly negative toll on quality and access to necessary care as well. Developing effective policy solutions requires an understanding of the existing financial incentives and how they are intertwined across stakeholders of various types. Because the profit motive is so strong and currently unrestrained in commercial markets, and because the financial standing of the broad array of health care entities have become so interdependent, no single incremental policy strategy will suffice to address the consequences of the status quo. However, a set of policy strategies at the federal and state level have the potential to constrain the current cost growth trajectory by eliminating perverse financial incentives and disentangling the profit-driven relationships that have put insurers, providers, and their middlemen currently at cross purposes to consumers, employers, and governments.

The full expert perspective is available to read and download here.